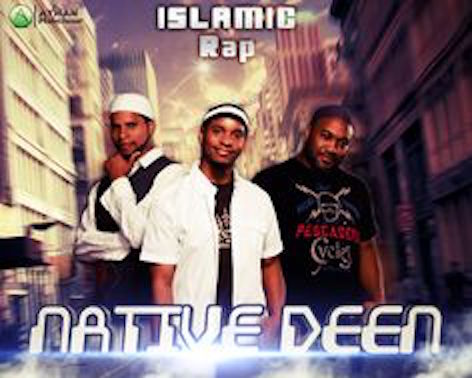

The Rise of Islamic Rap ←Click here to go to original article post

BRADFORD: Listening to South Asian Muslim teenagers in this post-industrial British city, one can understand how Islamic faith and American hip-hop music coexist. Searching for music that reflects their own experiences with alienation, racism and silenced political consciousness, many teens, even quasi-religious groups, turn to the urban music of black America.

Despite the recent popularity of a pop-oriented variant of nasheed devotional music, the acts with the largest followings are not Muslim nor do they focus on overtly Islamic themes. Rather, the teens offer a litany of popular culture icons – American hip-hop and rap artists including Jay-Z, the late Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur. Young South Asian Muslims throughout Britain have widely adopted and thoroughly adapted symbols and styles of African-American urban culture. Slang combining northern English colloquialisms, Bengali and American gangsta culture infuses daily conversations.

Social ills – drugs, gangs, unemployment – are common in British cities, and racial tensions can run high. A collective sense of identity emerges from this common urban experience, across different national settings – hence the transatlantic currency of the hip-hop movement, and presence of Islamic references in hip-hop culture, through quasi-Muslim religious groups such as the Five Percenters.

Seeking to validate the impulse that lies behind the popularity of this music, but direct its outward expression in more positive directions, a number of artists have recently experimented with Muslim versions of hip-hop. As Abdul-Rehman Malik, an observer of the UK’s Muslim music scene puts it, “they’re searching for a cultural and political expression that they can marry to their religious beliefs.” The fusion is sometimes a tough sell, however – not least of all because of persistent debates within Islam as to the permissibility of music.

Beginning with the group Mecca2Medina in London in 1997, the Muslim hip-hop movement has grown with impressive speed even as it struggles to achieve mainstream recognition within both the Muslim community and the wider hip-hop scene. Many Muslim artists cite passing references to Islam in mainstream hip-hop, and in their minds, the natural extension is to bring a religious identity front and center. For some, hip-hop is also a vehicle for engaging world politics. Figures like Fun-Da-Mental frontman Aki Nawaz attracted controversy for the 2006 album “All Is War,” which some viewed as glorifying terrorism. The music of another edgy act, Blakstone, features aggressive and confrontational lyrics.

While well-known American rap and hip-hop artists, such as Mos Def and Lupe Fiasco, express a Muslim identity, they do not make religion or politics an explicit focus of their music so as to avoid discomfort or rejection by the music industry. Many Muslim hip-hop artists, such as the female spoken word duo Poetic Pilgrimage, complain about persistent racism, even within Muslim communities in the West, contending that their work transcends ethnic and racial barriers.

This legacy of racial tension, while rarely a focal point of contemporary national-security policy, has reared its head in the form of multiple efforts in recent years to reinvigorate the figure of Nation of Islam activist Malcolm X. For example, shortly after Barack Obama’s 2008 election, Al-Qaeda’s deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri released a video statement castigating the US president as a “house slave” in contrast with the hard-line confrontational politics of Malcolm X.

This legacy of racial tension, while rarely a focal point of contemporary national-security policy, has reared its head in the form of multiple efforts in recent years to reinvigorate the figure of Nation of Islam activist Malcolm X. For example, shortly after Barack Obama’s 2008 election, Al-Qaeda’s deputy leader Ayman al-Zawahiri released a video statement castigating the US president as a “house slave” in contrast with the hard-line confrontational politics of Malcolm X.

Pointing to another side of the American civil rights leader, a British government–funded counter-radicalization project – combining traditional Islamic scholarship and social consciousness with hip-hop sensibilities – seeks to mobilize urban British Muslim youth around what they see as more cosmopolitanism impulses of Malcolm X after his break with the Nation of Islam and subsequent global travels.

Abdul-Rehman Malik

Abdul-Rehman Malik, a driving force behind the Radical Middle Way, expects popularity of Islamic hip-hop to grow: “Hip-hop is our way of seeing Islam in situ, in our place – a way of reflecting the anger of the Muslim street by creating discursive spaces for the expression of that anger. But it has to be real, and it has to resonate: your rap is only as good as the depth of its message.” Thinking about radicalism this way permits better understanding of other forms of oppositional politics framed in terms of Islam, as well as recognition of the appeal of Muslim politics as connected to broader histories of global exclusion.

These developments become more significant when one considers the demographics of Islam, with some 70 percent of the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims under the age of 30. Embracing hip-hop could be a fad or signal young Muslims’ growing affinity with leftist values. Islam, however, has never fit comfortably on a political spectrum defined in conventional terms of right and left. The Islamic worldview is socially conservative in most of its mainstream forms, but the centrality of social justice in Islam has always meant that Islamic parties share some common ground with the left – even where the politics between them are contentious.

Leftist parties in the Muslim world historically haven’t hesitated to couch their rhetoric in religious terms when so doing was perceived as useful – witness Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s description of Pakistan People’s Party policies in the early 1970s as Musawat-i-Muhammadi, or “Muhammad’s egalitarianism.” Iran’s Islamic Revolution was received as an essentially Third World project in many quarters, with supporters from Nigeria to Indonesia and even some outside the Muslim majority world citing Khomeini’s anti-hegemonic credentials.

Today we see sparks of growing cooperation between Islamists and leftists in the Middle East, although so far this speaks more to a realization by opposition leaders that it’s politically expedient to play down differences. This marriage of convenience extends to Islamist-leftist engagement on the global level, with both sides regarding the other warily even as they occasionally make common cause. In 2004, for example, the Bangkok-based NGO Focus on the Global South partnered with Hezbollah to host a strategic-planning conference in Beirut for anti-Iraq war and anti-globalization movements, prompting criticism from other left-leaning groups in Lebanon opposed to Hezbollah.

A common anti-war stance provided space for coordination between Islamists and the global justice movement on other occasions. For example, the Muslim Association of Britain, affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood, organized in concert with several anti-globalization groups the huge 2003 anti-war rally in London. The same association sent a delegation to the 2006 World Social Forum meeting in Venezuela, although again the motivation was more shared antipathy to the Bush administration rather than real ideological affinity.

In other cases, however, engagement between Islamic movements and the left has had more substance. In Europe, Muslim groups and the Green movement have shared platforms, and no less a figure than Tariq Ramadan has had ongoing if fractious dialogue with the altermondialisation movement, France’s distinct current of anti-globalization thought.

One also cannot help but notice the recent spate of texts on Islamic liberation theology – inspired by Latin America’s dissident Catholic-Marxist fusion from the 1960s and 1970s. Muslim thinkers from Ali Asghar Engineer in India to South Africa’s Farid Esack and the Iranian-American cultural critic Hamid Dabashi have articulated varied, often sharply contrasting accounts of the relationship between Islam and social-justice activism.

While these new arenas of Muslim politics do not yet represent mainstream political Islam, it’s significant that the actors and networks largely bypass the established “old guard” of modern Islamism such as the Muslim Brotherhood. In other words, young Muslims, dissatisfied with the failure of conventional Islamist groups to deliver results, may be searching for alternative avenues of political expression and mobilization – iPods firmly in hand.

Be the first to comment on "The Rise of Islamic Rap"